Tony, he would like it made clear, is not a masturbating Welshman.

There are two ways of watching Notting Hill.

There’s the grumpy, working-class-chip-on-your-shoulder way, which sees all the characters as privileged idiots who don’t deserve any more happiness heaped on top of their happiness mountain.

And then there’s the live-and-let-live, people are just people even if they’re rich enough to own houses in Notting Hill and never have to genuinely worry about any damn thing whatsoever… way.

The degree to which you’re able to empathise with phenomenally wealthy people and their loves, lives and concerns tends to define whether you enjoy Notting Hill, or whether you want to burn the whole film to the ground.

That’s also, actually, a factor of time and climate. When it was released in 1999, both Tony Blair in the UK and Bill Clinton in the US were harnessing the power of the middle class, which meant that for a brief, shining period, you could both be and root for people who were rich, because it didn’t necessarily mean they wanted to make life worse for everyone poorer than they were.

It’s worth remembering that fact in the 2020s if you want to enjoy Notting Hill with a clear conscience. Its cast of characters are both rich and mostly well-meaning, even if they do hold the most deathly dinner parties in the history of film.

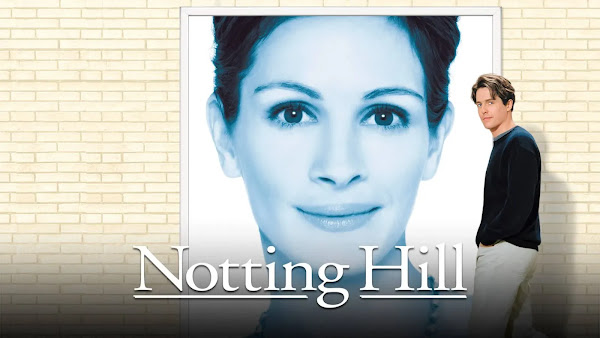

Ultimately though, Notting Hill is writer Richard Curtis’ first real leap from ‘surprise’ hit Brit-based rom-coms (like The Tall Guy and Four Weddings And A Funeral) to mainstream worldwide rom-com hits, by the telling of an unlikely love story between a modest but handsome British guy and a Hollywood film star. Oh, and by bringing in one of the world’s most bankable ACTUAL Hollywood film stars, Julia Roberts, to play the silly, adorable Brit-com game.

To say it succeeded wildly would sound like hyperbole, but actually still undersells the truth. It’s the highest grossing British movie of all time (to date). It won a Golden Globe, with nominations for each of the leads, Hugh Grant and Julia Roberts. It also earned a couple of BAFTA nominations and a British Comedy Award. Even the soundtrack won a Brit Award.

So – lots of people loved the heck out of Notting Hill when it was released. The urge to burn the film to the ground has grown in the last 20 years not because the film has magically become worse than it was when it conquered the world, but because of the polarising of the rich and the poor in the real world during the course of those decades.

Let’s leave the real world behind for a little while – after all, that’s what movies are ultimately FOR. Let’s remember a world where Hugh Grant was a floppy-haired Brit-throb on the rise and Julia Roberts was a Hollywood darling with the world at her feet.

The secret to Notting Hill’s success is that it’s a film about the coming together of two worlds that actually brings the best of two film-making traditions together. It’s a love story to its very bones, and however cynical you want to be about romance, lots of people are primed to respond to that.

In those storytelling bones, Notting Hill is a Hollywood rom-com in the grand Cary Grant tradition – people from different classes and walks of life are thrown together, and face a range of obstacles to their growing attraction both internal and external – geography, lifestyle, vast international press interest and at least one of the parties, to coin a phrase, being “a daft prick.” You can of course trace the lines of Notting Hill further back to a kind of stripped-down, inverted version of Pride and Prejudice – but then, that’s true of most modern rom-coms.

Notting Hill builds personality development into the interactions not just between the main characters but into a chorus of friends – at least on one side, accentuating some ‘fish out of water’ energy that adds to the seeming impossibility of the leads, Hugh Grant’s William Thacker and Julia Roberts’ Anna Scott, getting together.

William and Anna get at least two chances to get love right across the course of Notting Hill, and manage to get it wrong both times, which means it’s only after a point of culmination when things could have gone so very right and instead went absolutely wrong, that there is a moment of lightning-bolt clarity, leading to a last-minute change of mind, a panicked dash to a point of crisis, and a moment of contrition that makes things eventually work out right. That last-minute dash is crucial to the energy of the conclusion, because it drags us into the will-they, won’t-they drama and makes us shout at the screen, suddenly re-invested in the result, so that when the conclusion comes, it delivers the endorphins and emotions we want at the height of their power.

All of that is taken directly from an old and hugely effective Hollywood playbook.

But on top of that, it adds a very British comic sensibility. The British characters are all more or less quirky to some degree. Hugh Grant’s William Thacker runs a bookshop – so far, so good. It’s a travel bookshop, which significantly limits the degree to which it’s ever likely to actually SELL anything (as pointed out during the film by the visit of a thief who clearly hasn’t got the idea that it’s just a travel bookshop (played, cutely enough, by Dylan Moran, himself famous for playing a bookshop owner in Black Books).

Thacker’s friends are a motley bunch of quirky British stereotypes. His gloriously dotty sister, Honey (Emma Chambers, who was also starring in Curtis’ TV show, The Vicar of Dibley at the time) is fashionably off-beat and wildly excited when he brings a film star round to dinner. Max and Bella (Tim McInerney of Blackadder fame – also co-written by Curtis – and Gina McKee of Our Friends In The North) seem to be in the movie mmmmostly to hold dinner parties, to power the final race to the conclusion, and as a token of stoicism because Bella’s in a wheelchair. Bernie (Hugh Bonneville, later of Downton Abbey and Paddington), seems to be simply an idiot in the city, Toby is a chef and failed restauranteur, and Spike (Rhys Ifans), is famously ‘a masturbating Welshman’ who rents a room in Thacker’s Notting Hill house. He’s revealed in a throwaway line late in the film to be an artist of some sort.

None of them have any particular depth, but some of them have enough surface to keep the plot moving in interesting ways, particularly when Thacker brings international megastar Anna Scott (Julia Roberts) round for dinner, as though it’s a normal thing to do.

The story uses an accident to make Thacker and Scott meet each other, and a good, affectionate amount of gibberish to power their relationship along. What’s particularly potent is Scott’s role, her revelation of all the privations and hardships that can come with being on the Hollywood treadmill – the operations, the bad men, the disposable megastar status, and the way that, as shown in one particular scene where she takes on some men who are commenting on ‘That film star, Anna Scott,’ both her every heartbreak, her body, and her every move are the property of the public, both discerning and vulgar.

That follows through to the central internal threat to Anna and William having a lasting relationship. Once they’ve become a couple, and Anna has met ‘the friends,’ when they’re together in the Notting Hill house, they have a life of seeming normality – him running lines with her, them discussing potential moves that will give her longevity and above all some gravitas, so she makes the leap from disposable megastar to acting royalty. It’s all perfectly peaceful and harmonious – until the press show up in a baying pack outside the door.

While William, entirely inexperienced in the ways of the media, can’t immediately see the problem, viewing the media interest as something that by tomorrow will be lining cat baskets, Anna, with her experience of what the press have done to her in the past, flees the idyll of their Notting Hiill oasis, with its impossible promise of a somewhat ‘normalized’ life, and gets back on the Hollywood treadmill. Her choices have been improved, though, and she gets herself on a higher ‘class’ of picture, the kind of thing that gets not only Oscar buzz, but nods from the more overtly theatrical media.

There’s another misunderstanding when William thinks he overhears her dismissing the potential of their relationship on set, and Anna comes back to break down all the lifestyle complication and just be “a girl, standing in front of a boy, asking him to love her.”

And from there to William (spoiler alert) being “a daft prick” and having to have his friends hurtle him across London to undo the damage he’s done and propel him to his happy ending with Anna Scott is a simple matter of delivering the adrenaline-fuelled “you shall go to the ball!” mayhem that always gives the final act of a rom-com the uncertainty it needs before everything comes right.

Notting Hill is a love story of the merely rich and the justly famous but underneath all that, it’s a classic Hollywood rom-com with extra cutesy, quirky Britishness – not least in the person of Hugh Grant, whose William Thacker, despite being at least mostly hopeless is hopeless in that adorable way that probably only Hugh Grant could pull off. It’s a story of class and lifestyle clash, but it’s also a story of love and gibberish – when William, invited to come and see Anna, pretends to be a journalist from Horse & Hound magazine, interviewing her (and the rest of the cast) about their new space blockbuster movie, it’s committed gibberish with a heart of gold. It’s a story with its roots in classic Hollywood, with elements of Pride and Prejudice and a 90s Britcom sweetness. And it’s a story about making love work out despite external pressures and internal insecurities.

And that’s ultimately why audiences continue to love it, to this day. When you strip it all down, it’s a story of how absurd the challenges to love can be, and how, when it feels right, and if you’re ultimately strong enough, you can make it work come hell or high water, because when it’s worth it, it’s just…worth it. All of it.

Yes, in the 2020s, Notting Hill has issues. It has non-disabled actress Gina McKee in a wheelchair, more or less exclusively to push some audience buttons. And it does feature an actor who’s since become as well known for transphobia as he was for his acting.

But everyone can relate to the fundamental story of the moment when life goes “Bam!” and puts the person of your dreams – the person you’ve never even dared to HAVE dreams about – right there in your path, and they seem to like you. The stumbling, gibbering, do-whatever-it-takes path to take that moment and make it last the rest of your life is fundamental to all human beings, irrespective of sex, sexuality, gender, class or ethnicity.

That moment of “Bam” – and the efforts of William Thacker and Anna Scott to make it last forever – will always speak to romantics and wannabe-romantics everywhere.

Watch Blackadder today with a seven day free trial of BritBox.

Tony lives in a cave of wall-to-wall DVDs and Blu-Rays somewhere fairly

nondescript in Wales, and never goes out to meet the "Real People". Who,

Torchwood, Sherlock, Blake, Treks, Star Wars, obscure stuff from the

70s and 80s and comedy from the dawn of time mean he never has to. By

day, he

runs an editing house, largely as an

excuse not to have to work for a living. He's currently writing a Book.

With Pages and everything. Follow his progress at FylerWrites.co.uk

Post Top Ad

Tags

# Feature

# Hugh Grant

# Julia Roberts

# Movies

# Notting Hill

# Tony Fyler

Tony Fyler

Labels:

Feature,

Hugh Grant,

Julia Roberts,

Movies,

Notting Hill,

Tony Fyler

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment