Tony’s regressing to childhood again. Because look at it out there.

Imagine an animated soap opera for young children.

Then take out all the sex, violence, and other pre-requisites of a grown-up soap opera, and instead, add a little bit of commonplace magic, in a tiny corner of the top left of Wales in the age of steam trains. What you have then is Ivor the Engine.

If we say that this is an Oliver Postgate/Peter Firmin production, you probably get an almost-instant sense of the tone of the show. Bucolic is probably a good word for it. Well-meaning. Charming. All those things, and a touch more besides.

The partnership that brought a generation of children Bagpuss and his magical shop that repaired everything and sold nothing, and that introduced them to the gentlest knitted science fiction (and potentially, soup-addiction) in The Clangers, also created a sweet, soft, semi-magical 2D animated Welsh soap opera about a little green steam engine with a mind of its own, a dragon in its firebox, and an absolute dedication to ‘singing’ in the local choir.

Ivor the Engine is, to this day, like wrapping up in a warm Welsh woollen blanket and having a bowl of hot soup on a cold and soak-you-to-the-skin, hate-the-world night. People in the 2020s talk about self-soothing, me-time, disconnecting from the high-pressure world and suchlike entirely valid recharging strategies. Let us tell you now – bowl of soup, blanket of choice, Ivor the Engine on Britbox, you’re sorted.

Even for those who have no memory of the show when it aired – which statistically is probably most people – it has a combination of charm, simplicity, safely-bounded drama, and characters you can’t help but love, mostly narrated and given voice by Oliver Postgate himself, whose soft Welsh burr is like a favourite grandfather popping in to see if you need a hot water bottle, a hug, or an extra piece of chocolate, don’t tell your mother.

Bad day at work? Ivor’s the cure.

Partner insists on breathing, when you’ve asked them nicely not to? Ivor.

Whole world seeming to go to hell in a handcart and too scared to look at the news? Close the app, open up your Britbox, and spend a little while with Ivor the Engine.

As shows go, it’s pretty much the panacea for all ills.

Talking about its exact origins and content is surprisingly tricky, though. Originally launched in 1958 in black and white (it was a strange and disturbing world, o sweet digital younglings), Ivor the Engine was the first venture by Postgate and Firmin under the auspices of their production company, SmallFilms.

The first six episodes were very much an origin story, and weirdly, without them, one major thing about Ivor the Engine never gets to make a great deal of sense. Ivor is a keen member of the Grumbly And District Choral Society when most of us first meet him, but that initial six-episode story tells of how the engine that wanted to sing had his single-note, boring whistle replaced with the pipes from a fairground steam organ. That upgrade lets him add his ‘voice’ to the choir, and he’s never intentionally late for either a practice or a performance from that day on.

The weird thing about that is that, while those six episodes led to two series in black and white, when in 1975 the BBC decided it wanted more Ivor, the two black and white series (which had run to 10 minutes per episode) were re-created in colour, and cut to 5 minutes in length… that initial six-episode origin story never made it into the run of 40 5-minute episodes, so lots of children grew up simply accepting that this magically self-aware steam engine just had this musical ability.

But no. And now you know where he got it from. So, whenever you see and hear Ivor using his unusual pipes to communicate or sing – that’s why.

It’s worth acknowledging too that while he was enough of a success in black and white to make the BBC want more of him some 15 years after his initial run, it’s really as a colour programme that Ivor the Engine lodged itself in the minds of children all across Britain in the Seventies, and for decades afterwards in re-runs.

The inspiration for Ivor is almost as sweet and bucolic as the show itself.

When Postgate met a fellow Welshman who’d worked as a fireman on an old locomotive, he was inspired by the man’s tales of how the old steam trains used to ‘come alive’ when they were getting their steam up in the morning, to almost develop their personality as the heat and the steam that gave them motion and power seeped into their metal ‘veins.’ The idea of an engine that did exactly that, that came alive but had no ‘human’ voice to express itself, was irresistible, and the idea of the engine that wanted to sing was born.

But, as with many Postgate and Firmin productions over the years, there’s more to Ivor the Engine than just the main character. In fact, Postgate took some inspiration from Welsh writer Dylan Thomas and his play for voices, Under Milk Wood, to develop a whole community that Ivor could serve. And, with an entirely authentic Welshness that also appealed to the straight-line minds of children, most of the characters went by combination names, such as [Name] the [Occupation], or even [Name] [Occupation]. So where in Under Milk Wood, you get Dai Bread (the baker), Ocky Milkman, and Evans the Death (the undertaker), in Ivor the Engine, you get Ivor’s driver, Jones the Steam, Dai Station (the station master in the town of Llaniog), Owen the Signal (the signalman), Evans the song (the choirmaster) and so on.

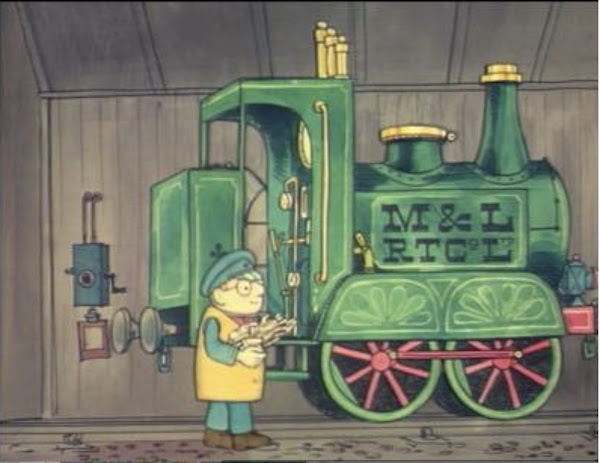

By rounding out the lives of the people of Llaniog and Grumbly – areas served by the Merioneth and Llantisilly Rail Traction Company Limited, and therefore by its dogged steam engine, Ivor, Postgate not only created a wider world in which Ivor could live, he also gave scope for each of the characters to have personalities, and provide either dramas or solutions to dramas in which Ivor and Jones the Steam could become embroiled in each 5-minute episode.

And then there’s the magic. As well as the literalism of Ivor being an engine who’s alive, and who has his own views on things (check out the episode where he gets dead stroppy and Jones the Steam rebukes him, only to discover that Ivor has been stopping so that he doesn’t endanger some local wildlife!), there are, from very early on in the series, dragons. Not big, scary, stab-them-with-swords-if-you-want-to-be-fricasee dragons, but small, red hot, vulnerable, heraldic Welsh dragons.

First, there’s Idris, who’s discovered as an egg and who hatches out in Ivor’s firebox, adding his voice to the choir. And eventually, there’s a whole family of small dragons, who need rehousing if they’re to flourish in the wild. It takes the co-operation of most of the villagers – and a dragon-friendly engine – to save them when their mountain goes suddenly cold, threatening their lives.

Wholesome much? You want dragons? It takes a village…

Even the construction and production decisions on Ivor the Engine are meant to evoke a calm world of yesteryear. Peter Firmin created the visuals in watercolours, giving the North Wales countryside probably the first representation most of the show’s original viewers would ever have had in the pre-internet age. The animation was 2D stop-motion using cardboard figures. And the soundscapes were often delivered by a single bassoon to emulate Ivor’s organ-pipes, with regular choral action from the choir that is so much a part of Ivor’s life.

Oh, and if you want to flush out an Ivor fan in the wild, all you need to do is walk into any room and say “Psssh-t’kuff.” Spellings may vary, but the sound of Ivor’s wheels in motion as he puffs from place to place is iconic to several generations – and yes, Postgate made the noise himself, by saying something those words or something like them. Ivor fans everywhere will be unable to stop themselves responding with a “Psssh-t’kuff” of their own, because the sound is evocative over decades of intervening experience, and bonds fans of the little engine who most certainly could in their sudden, bright-eyed moment of joy.

Surprisingly for such a low-tech production, there were three main voice actors on the show. Postgate provided the main narrative voice, as he did for Bagpuss and the Clangers, but for differentiation, Anthony Jackson (who would later endear himself to a generation of children as Fred Mumford, the founder of Rentaghost) was brought in to voice some other male characters like Dai Station and Evans the Song.

Meanwhile, Olwen Griffiths added legitimately high-pitched voices for most of the women in Llaniog and surrounding areas, including Mrs Porty (the low-key owner of the railway, and a friendly hat-obsessive).

Ivor the Engine is a balm to the fevered mind, a retreat from bad news, bad days and bad people, a nostalgic joy to those who saw it on broadcast, and a stress-free, neon-free treat for parents who want their kids to sit still for almost three and a half hours, while learning about kindness, togetherness, community, acceptance of the different, and the importance of protecting vulnerable creatures.

Honestly, if you can find a better gift to the world at large, we’d quite like to know what it is.

And now, the whole collection of those 40 colour episodes (no black and white origin story – sorry!) is available on your Britbox subscription. Give it a binge today. And then, given the state of the outside world… maybe do it again.

Watch Ivor The Engine today with a seven day free trial of BritBox.

Tony Fyler lives in a concrete cave, somewhere on the edge of

the sea, with his wife, who exists, and the Fictional People In His

Head, who don't as yet. A journalist and editor by day, he has written

Some Books, and is more or less always writing another. One day, he may

even get around to showing them to people. In the meantime, he's Script Editor and occasional Executive Producer at Third Time Lucky Productions, and a proud watcher of things no-one remembers they remember until they remember.

Post Top Ad

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment