Tony’s taking the top bunk.

Let’s be clear on one thing. There is no movie adaptation of an Hercule Poirot novel with more chance of being an all-star powerhouse success than the 1974 Murder on the Orient Express. Even Kenneth Branagh’s 2017 re-do of the same text, including Johnny Depp, Judi Dench, Michelle Pfeiffer and Olivia Coleman pales weirdly into relative insignificance before the might of the 1974 cast.

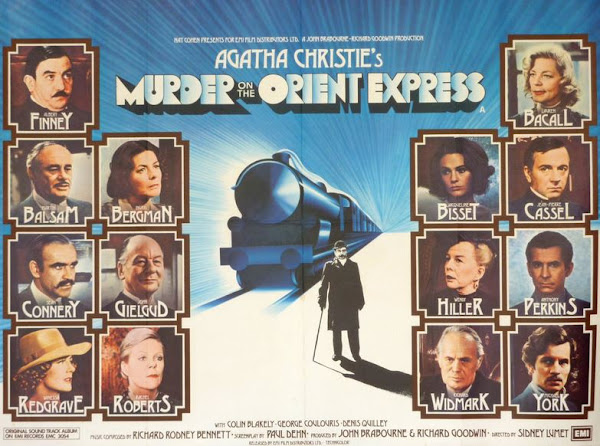

Any movie that gets Lauren Bacall, Ingrid Bergman, Sean Connery, John Gielgud, Anthony Perkins, Vanessa Redgrave, Richard Widmark, Michael York, Jacqueline Bisset and, did we mention, Albert “the one and only” Finney in its cast surely has to be on to a winner, right?

Matching a cast like that with one of Agatha Christie’s more intentionally convoluted but gloriously satisfying plots, with a murder on board a luxury train, with no chance of interference from outside or escape for anyone, thanks to a snow drift, must surely sparkle with tension and terror. Right?

Mmm.

Well, here’s the thing.

In the first place, the one thing Agatha Christie very rarely did is spoon-feed you context in advance. Murder on the Orient Express is supposed to be exactly as it seems to Hercule Poirot as he gets on board the fabulously opulent train heading from Istanbul to Calais – a coming together of, to coin a phrase from another murder thriller, strangers on a train.

The idea is gloriously simple. We assume whenever we get on board any form of public transport that “the public” who share it with us are a random sampling of the kind of people who use that transport regularly – people who can afford it, and who need to get from point A to point B.

That randomness is built into our understanding of how the world works. It’s a fundamental part of the standard operating procedure of our lives – the public will be made up of small clumps of people who know each other, but those clumps will not coalesce into a whole mob of people who are connected.

It’s that fundamental sense of the normalcy of randomness in any group of people in any given situation, such as the passengers on a train, that Christie exploits to spring one of her best traps in Murder on the Orient Express.

Which means it’s singularly bizarre that a director of no less skill and reputation than Sidney Lumet, the man behind 12 Angry Men, Dog Day Afternoon, and Network, should choose to preface his version of Murder on the Orient Express with a lengthy if dialogue-free re-cap of the events of the night of the kidnap of “the Armstrong baby.”

In something of a riff on the case of the Lindbergh baby, little Daisy Armstrong was stolen from the home of wealthy British army colonel Hamish Armstrong and his American wife, Sonia. A ransom was demanded and paid, but Daisy was later found dead, and the case scandalised the hearts of two nations – and every nation that wanted to feel safe in the prospect of its children’s safety in their own home.

Showing us this right up front pre-disposes us to think the mystery we’re about to see will have something to do with the Armstrong case – and really speaking, not knowing that in advance is key to the mystery of the Orient Express case. It’s only supposed to really come in when Poirot finds – and then has the nous and the equipment to decipher - a clue, after the murder on the train is committed.

Knowing in advance that something about the Daisy Armstrong case, where the kidnapper and killer remain unknown to the world, will tie in to the events we’re about to witness, punctures the sense of suspense right from the off, and this being a story of Hercule Poirot, legendary possessor of the impeccable “little grey cells,” leads us to assume we will discover the murderer of Daisy Armstrong on the famous strain from Istanbul to Calais.

Now, it’s with a heavy heart that we have to admit that this leaden approach to Christie’s storytelling seems to take hold of most of the cast, too. Getting such a stellar combination of talents together for an intriguing Agatha Christie story is one thing. Getting the best out of them is quite another.

The annoying thing about which is that we know it can work. When Albert Finney declined to come back for what was always supposed to be his second Poirot movie in 1978, Death on the Nile, a different screenwriter and director got wonderful performances out of their all-star cast, including Peter Ustinov, who breathed warmth and sympathy into Poirot.

Here, it often feels as though the literally narrow confines of the train carriage put the cast in emotional straitjackets. Yes, to some extent, this is right for their characters – Sean Connery as Colonel Arbuthnot and John Gielgud as Edward Beddoes both have military backgrounds, so a stiffness and uncommunicative nature are right for the parts. The fact that neither of them smile more than once throughout the film feels technically right once we know they both have secrets they’re hiding, but it never makes for any light and shade in the film.

There are those who still manage to act their way beyond the oppressive direction, though. As you might reasonably expect, both Bacall and Bergman as Mrs Hubbard and Greta Ohllson respectively have wonderful moments, and Bergman in particular makes cinematic gold of a five-minute scene she was given, essentially to frighten her off.

Originally offered the much more imposing role of Princess Dragomiroff, Bergman decided she wanted the smaller, slightly disturbing and otherworldly role of Greta Ohllson. Director Lumet gave her the five-minute piece to dissuade her and push her towards the Princess role.

Ingrid Bergman was not an actress who backed down from challenges. She took it, blew the doors off it, and ended up with an Oscar for Best Supporting Actress for her pains.

In all fairness, her big scene is one of the most affecting pieces of drama in the whole movie, both for Bergman’s performance and because it forces Albert Finney to adopt a new way of being Poirot, compared to his approach to the role throughout the rest of film.

Say what?

Yes, unfortunately, alongside the leaden direction, there is the problem of Albert Finney as Poirot.

Now, let the record show that Albert Finney was a phenomenal actor, and a fairly phenomenal human being too.

What he was not was any kind of Hercule Poirot. Early in the film, his Poirot, while celebrating with a friend, comes off as brash and loud beyond the boundaries of public thoughtfulness. And while, ironically enough, he’s pretty good at being the vexed and peevish Poirot when he’s simply standing still and not saying anything, his approach to Poirot in action is deeply bizarre. His voice hovers between Don Corleone and Hitler, and there never feels like any connection to the reality of any character, let alone Christie’s Poirot.

The structure of Murder on the Orient Express doesn’t help him. There is, after all, only one murder in the book – an almost unheard-of rarity in a Christie book. That means by its very nature – one murder, stuck in a snowdrift – the second half of the book is very formulaic. It’s a sequence of interviews between Poirot and all the suspects. There are occasional flourishes that aim to confuse or push on the drama – the discovery of a Wagon-Lit guard’s uniform and a red kimono, both of which suggest a disguised assassin and a convoluted external plot to kill a single passenger, Mr Ratchett (played here with plenty of bluff rich man bluster by Richard Widmark). But essentially, that structure leaves the reader – and the viewer – with little else to focus on but Poirot and his questioning techniques.

Finney’s tones of rage and frustration throughout the second half as he rails against each passenger in turn, showing them they could have committed the murder, get quickly exhausting and don’t carry the audience with him. We should, we instinctively feel, be on Poirot’s side, and Finney’s portrayal of him as a witness-haranguing interrogator makes him seem not so much the genius with the little grey cells as an overblown clown, making random guesses in the dark and doubling down on them in the face of what each suspect tells him.

That’s the other reason why the interview scene with Bergman is so affecting – it’s the one scene in which Finney’s Poirot is gentle and coaxing, as though speaking to a child, rather that grating and ranting, as he is with most of the other passengers.

By the way, don’t feel compelled to take our word for it. In a biography of Christie, she’s recorded as thinking the film “was well made except for one mistake. It was Albert Finney as my detective Hercule Poirot.”

Connery felt there had been perhaps more than one mistake, claiming he’d been “stupidly flattered” by being described as an anchor for the film, one who would bring in other stars. In fairness, filmed versions of Christie stories were frequently able to draw big stars on their own merit.

And there are, in further fairness, glorious moments of meta-casting in the movie. Finney’s Poirot sitting opposite Hector McQueen, Ratchett’s secretary, played by Anthony “Norman Bates” Perkins and asking him “Do you love your mother?” is a great little meta-gag that surely must have been planned.

But on the whole, Murder on the Orient Express feels like a movie that found a way to do the almost impossible and the practically unthinkable – it made one of Agatha Christie’s finest, most ludicrous and yet most compelling mystery stories, cast with some of the best actors alive in the world at the time, feel heavy and leaden, the whole feeling like less than the sum of its parts.

The great moral conundrum that faces Poirot at the end of the story – whether to obey the law, or to chalk one up to ‘natural justice’ – feels slight, underplayed and shrugworthy here too. At least in the Branagh version of 2017, it’s that moment that sends Poirot into screaming frustration. Here, it’s decided with barely a shrug and a half-hearted vote, and the greatest detective in the world allows a murderer to go free on the basis that a carriage full of people would really rather like him to.

Is there no real redemption for the 1974 Murder on the Orient Express, then? Well yes, some - as we’ve mentioned, some of the actors rise above what feels like a determinedly leaden direction – Bacall, Bergman, Rachel Roberts as Hildegarde Schmidt, and Vanessa Redgrave as Mary Debenham in particular are value for money. Richard Widmark as Ratchett is impressive for as long as he’s in the film.

But overall, Murder on the Orient Express is an object lesson in how to mess up an adaptation of Agatha Christie. Aside from everything else, little effective use is made of footage of the countryside through which the train is supposed to be moving – it was mostly filmed at Elstree, so there’s logic there – and while Richard Rodney Bennett’s Orient Express Suite is perfectly fine and does its job, it never provides a hook that lets you remember it after the movie has ended.

The irony is that Finney was due to reprise the role in 1978 on Death on the Nile, but didn’t want to go through the extensive make-up process in the heat of the Egyptian sun.

The result was the casting of Peter Ustinov, and the ushering in of a decade of lighter, more approachable Poirot movies. Watch Murder on the Orient Express, by all means – there are people who love it. But then watch Death on the Nile and Evil under the Sun too, to see the dramatic change that a different actor, screenwriter and director were able to bring to the whole business of Hercule Poirot on film throughout the 1970s and 80s.

Watch Murder On The Orient Express today with a seven day free trial of BritBox.

Tony Fyler lives in a concrete cave, somewhere on the edge of

the sea, with his wife, who exists, and the Fictional People In His

Head, who don't as yet. A journalist and editor by day, he has written

Some Books, and is more or less always writing another. One day, he may

even get around to showing them to people. In the meantime, he's Script Editor and occasional Executive Producer at Third Time Lucky Productions, and a proud watcher of things no-one remembers they remember until they remember.

Post Top Ad

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment